|

Pioneer

Cemeteries and Their Stories, Madison County, Indiana |

|

|

Pioneer

Cemeteries and Their Stories, Madison County, Indiana |

|

Madison County Pioneer History

The New Purchase

The larger area that included what is now Madison County was opened for settlement when Native Americans of the Delaware and Miami tribes ceded their lands in Indiana to the United States government in the St. Mary's Treaty, October 3, 1818. While the Native Americans were allowed to stay for three years before moving west, pioneers from the East began arriving to homestead the "New Purchase." Even before surveyor David Hillis could begin his task in 1821, John Rogers according to his personal dairy settled along Fall Creek in 1818, William Dilts may have entered the Chesterfield area as early as 1819 as some historians will attest, Benjamin Fisher according to a historical newspaper settled along Stony Creek in 1820, and in the same year Jacob Hiday arrived in Green Township.

The pioneers first homesteaded the land along the waterways out of necessity. Settlers needed accessible water for survival, milling produce and timber, and sometimes for travel. Homesteads were planned so that this everyday, basic necessity was easily obtainable. Therefore, the townships which contain White River and its larger tributaries were inhabited first. Fall Creek, Union, Green, Jackson, Stony Creek, and Anderson townships--the southern half of the county--acquired the most early settlers and, therefore, have the most pioneer cemeteries. The townships in the middle of the county had "rich land" but fewer large waterways. Richland and Monroe townships with Killbuck and Lily creeks, Lafayette Township with Indian Creek, and Pipe Creek Township--actually named for its waterway--began to attract settlers in the early and mid 1830s. The northern tier of townships had a deterrent to settlement: an extension of the Miami Indian Reservation. As a result, Boone and Van Buren townships started acquiring settlers only in the mid and late 1830s. Finally, in the northwest corner of the county, Duck Creek Township had swampy land as well. This area was the last to be settled and so has the fewest pioneer cemeteries.

|

|

This is what pioneers to the eastern half of the New Purchase faced in the early 1800s: an untouched forested wilderness sprinkled with Delaware villages along the major waterway. From the 1932 map entitled Indiana The influence of the Indian upon its History-with Indian and French names for Natural and Cultural Locations, #122, published by the Indiana Department of Conservation, the White River area of Madison County is shown as a well-developed part of the larger Delaware society in east-central Indiana. The Delaware had as many as fourteen villages along this west fork of the White River. The Delaware--or Lenni-Lenape meaning "real men"--were living along the East Coast in what is now the state of Delaware at the time of the first discoveries of the New World. As the white civilization advanced, the Delaware moved westward, living near Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1682, on the Susquehanna River in 1742, and in eastern Ohio in 1751. In 1770 the Miami and Piankeshaw tribes of Indiana invited the Delaware to settle between the Ohio and White rivers. Many modern place names in east-central Indiana are either Delaware names or their English equivalents: Muncie, Wapihanne, Killbuck, Kikthawenund, Anderson, etc. The map shows the Wapihanne--or White River--flowing westward past the Delaware villages of Munseetown, Buckstown, Andersontown, and Straw's Town before turning south and reaching the first white settlement in east-central Indiana, the William Conner trading post and farm of 1802 where the Conner Prairie living museum now exists. Continuing south, the White River passed what would eventually be Indianapolis, or Chanktunoongi meaning "makes a noisy place" in the Miami tongue. The triangles indicate Delaware villages, the circles mark white settlements, and the cross designates the one religious mission--the Moravians from 1801 to 1806. The White River's major tributaries are clearly shown: Fall Creek, Pipe Creek, Killbuck Creek, and Duck Creek where pioneers would settle starting in the southern half of the county and eventually moving into the northern. The dotted line along the north bank of the White River is the well-established Indian trail going from what is now Greenville, Ohio, to Chicago, Illinois. Using ox-drawn wagons and possibly pack horses, this would have been the route many of the first pioneers coming from the East would have taken into the Madison County section of the New Purchase. The northwest corner of the county was part of the Miami Indian Reservation as marked by the line of dashes. The county seat of Anderson began as a Delaware village called Wapiminskink meaning "chestnut tree place" and later referred to as Andersontown after Delaware Chief Anderson. The original layout of Anderson followed the Delaware village's boundaries and trails. (For more on Anderson, go to the Anderson Township page. For information on the Strawtown Massacre, go to the Stony Creek Township page.) |

"The fine water power of Madison County, not surpassed probably by that of any county in the State, its fertile soil, excellent limestone and marble which are found here easy of access, will all be called into requisition..., and this part of the country will advance rapidly in improvement," affirmed the 1849 Indiana Gazetteer published by E. Chamberlain. Madison County was, indeed, attractive to settlers entering the New Purchase, so much so that by 1823, only five years after the new territory's opening, the population in the county was large enough to warrant organization. Madison County, in fact, was one of the first counties in the New Purchase to be legally recognized, and population growth continued. By 1830 there were 2,442 residents, by 1840 8,874, and at publication of the Gazetteer, 1849, there were 11,500. [Since the web site author is a former teacher, it is interesting to note that the number of residents in the county in 1830 was not much more than the student population at a large modern-day high school.]

|

These "monarchs of the forest," now tipping with age into the water of the Wapihanne (White River), might well have seen the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) paddling their canoes between Buckstown (near Chesterfield) and Wapiminskink (chestnut tree place, Andersontown). This picture was taken in Edgewater Park in Anderson. Along the opposite bank in the background was the location of the original Delaware village and later settlement of Andersontown. |

|

The First White Family

Even before William Conner, the first permanent resident to central Indiana, settled on his farm in what is now Hamilton County in 1802, Moravian missionaries to the Delaware tribes had located along White River in Madison County in May of 1801(see map above). John Peter Kluge, wife Anna Maria Ranck, and twenty-four year old co-missionary Abraham Luckenbach traveled from Goshen, Pennsylvania, where they had passed the winter with Moravian leader Zeisberger. They were accompanied by Delaware converts to their Protestant faith, Thomas and Joshua, who acted as guides and interpreters. On the north bank of White River near a distinctive, large chestnut tree in what is now mapped as the southeast quarter of section 17 in Anderson Township, they built a substantial log house or small fort. The mission eventually included other out-buildings, a vegetable garden, hay and corn fields, a place for their cattle, and "God's Acre," the traditional Moravian name for a cemetery. According to Madison County Historian Steve Jackson, their cemetery was probably on a hill just north of the mission and was intended for themselves and their converts.

While nothing of the Moravian mission remains, its exact location on the north side of White River within the southeast quarter of section 17 in Anderson Township has been thoroughly researched by Madison County Historian Steve Jackson. From the missionaries' entries in their White River journal of the topography and land marks near and around their log buildings, Mr. Jackson has determined that only one spot qualifies. The site is straight south of the cul-de-sac on the south end of Linwood Drive in the Bridlewood Farms housing addition. Bridlewood Farms is southwest of the junction of Chesterfield Drive and 10th Street in Anderson. A footpath leads from the cul-de-sac to the forested river bank. As seen in the picture above, walking paths extend along this north bank of White River.

As well as their Moravian faith, the missionaries tried to teach the Native Americans farming and animal husbandry. However, owing to a clash of cultural differences and a mistrust at this time of whites in general, there was only a small number of natives who took genuine interest or attended the Moravians' services. For the most part, the Delaware presented little but apathy to the well-meaning and dedicated Moravians. However, when in 1806 Joshua, the Moravian's guide and interpreter, was accused of witchcraft by tribal leaders and put to death and a friendly Delaware chief was also killed by his own son, the missionaries began to fear for their lives. In September of that year they abandoned the mission, returning to Pennsylvania.

|

|

One of the stories related in the Moravians' journal of their White River mission tells of the death of a young Native American boy. He, his mother, and sibling were near the mission tapping maple trees for their syrup. The boy had been misbehaving and for discipline was told by his mother to remove himself from her company. He did so, wandering off towards the river. After some time, the boy had not returned and could not be found by the mother, who at this point feared that something had happened to him. She came in tears to the Moravians, begging for their help to find her son. Kluge and Luckenbach searched the area along the river where the family had been working and eventually discovered the little boy's body lodged against a large rock in the middle of the river. The child had evidently tried to cross and was drowned. From the Moravian's detailed diary entry of this tragic event, Mr. Jackson is convinced that the rock pictured here, located to the east of the mission site, is where the boy's body was found. |

Of special importance to Madison County, during their time here John Kluge and wife Anna Maria began their family. They had three children while at their White River Moravian Mission: Karl Freidrich in 1801, a daughter Henrietta in 1803, and another son John Henry Kluge, in 1805. While the latter's gravestone records him as the "first white child born in Indiana," that distinction actually cannot be given to any of the three Kluge children due to a lack of records for the first Hoosier settlements along the Ohio River in the late 1790s. His brother Karl Friedrich, born 1801, however, was certainly the first white child on record for Madison County and probably the first born in the New Purchase of central Indiana. John and his siblings, nonetheless, were among the first born in the state. Additionally, while this very first white family of Madison County had to leave after five years, the Moravians were not discouraged. In 1830, members of the faith founded the town of Hope, Indiana, in Bartholomew County, and it is here that the adult John Henry Kluge and his family lived and died. They are buried in their faith's cemetery there, also by Moravian custom called "God's Acre."

|

At right is a picture of the gravestone for John Henry Kluge in God's Acre, the Moravian Cemetery in Hope, Bartholomew County, Indiana. The inscription reads: "First white child born in Indiana, John Henry Kluge was born at the Indian Mission Station on White River at Anderson, Indiana Dec. 31, 1805 And died at Hope, Ind. Nov. 20, 1898 Aged 92 yrs. 10 mos. & 11 ds. Asleep in Jesus, blessed sleep!" Perhaps a descendant or church member made the inaccurate assumption, or perhaps John Henry himself thought that he was the first white child born in the state. For whatever reason, while this son of missionaries John Peter Kluge and Anna Maria Ranck was not the first white child born in Indiana, he was, nevertheless, among the first, and his grave marker gives testimony to his family's dedication to their faith. |

|

John L. Forkner recorded in his The History of Madison County, Indiana, a conclusion for the county's first white family:

"In the fall of 1912 the chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution of Anderson decided to mark the site of the mission with an appropriate monument... The monument was unveiled on Sunday, June 1, 1913... A special guest on this occasion was Miss Alice Kluge, of Hope, Indiana, whose father was the first white child born in Madison county, having been born at the old mission... The inscription on the monument is as follows:

In Commemoration of

The Moravian Missions

To the Indians

Maintained on White River

South of This Spot 1801-1806,

Erected by

Kikthawenund Chapter

Daughters of the American

Revolution

1913."

The large rectangular block of limestone holding this plaque is on the south side east 10th Street between Scatterfield Road and Chesterfield Drive in Anderson.

From Frontier Traders to First Businessmen

The Makepeace family is of special importance to Madison County. While the vast majority of our first families were farmers, the Makepeaces were the pioneer version of business tycoons. When other pioneer settlers were clearing the land in order to grow crops, the Makepeaces were constructing mills and schools, designing towns, organizing post offices and banks, investing in hotels, and operating stores filled with the basic commodities needed for everyday life in the early 19th century. Even before Anderson's founder John Berry settled here in March of 1821, brother Allen and Alfred Makepeace travelled from New Hampshire to this region as merchants in 1820. They had wagon loads of basic food items, iron tools, fabrics, hides, simple kitchenware, knives, and fancy trinkets. They camped along the Wapihanne (White River) where they sold these goods to the Lenni Lenape (Delaware Native Americans) who lived in Wapiminskink (Anderson), the village of Chief Kikthawenund (Captain William Anderson).

The brothers must have been impressed with this forested wilderness, the navigable river and its many tributaries because they stayed and continued as frontier traders with with the Native Americans. Perhaps they saw in this unsettled region, which was soon to be opened for settlement, opportunities for entrepreneurs like themselves. They undoubtedly considered this a good area into which their entire family could relocate because that is what happened. In 1823, Allen and Alfred's father Amasa Makepeace, Sr., 1777-1848, brought the rest of the large family from the East to join the brothers' enterprise. Amasa homestead over 130 acres along Mill Creek in what is now Union Township. With the family's "mercantiles," shops, mill, and involvement in the first banks and early county government, the Makepeaces were some of the county's first businessmen of wealth. Their success contributed to the progress and prosperity of the entire region.

|

Amasa Makepeace, Sr., is responsible for building in 1827 in Chesterfield, Union Township, the first house in all of Madison County. This was not a one story, rough-hewn log cabin with a dirt floor as most early settlers were living in. This home was an impressive two story structure framed and finished with planed lumber and insulated with plaster instead of mud chinking and daubing. While the Makepeace house, pictured right, has obviously undergone many renovations, it still retains something of its Federal architecture and is still used as a residence |

|

Pioneer Life

Madison County is fortunate to have had several histories written by local authors before the county was 100 years old. One writer in particular Samuel Harden included in his book The Pioneer several letters. These letters were written in the 1890s by pioneers who had come as children with their parents to Madison County in the 1820s and 30s and who relate the living conditions of that wilderness experience.

From W. D. Brunt, November 5, 1895:

"When we first settled in Boone township [1838] our nearest neighbor was three miles away. The stock all ran in the woods and got fat on the wild pea-vines. We moved into a pole hut; we called it a camp. We lived in that until father erected a log house. We then lived in that until in time it...was replaced by a better one. In those days wild game was plenty, such as wild deer, turkey, wild-cats, wolves, panthers, bears... and plenty of rattle-snakes. The first Sunday school I and my brother attended we walked three and a half miles. It was taught in a log cabin... Mother taught us to spell and read before we ever saw a school house. We attended district school from four to six weeks in a year. Sometimes we walked three miles and thought it no hardship...

"I was married March 10, 1853 to Miss Adaline Reynolds...and to our union eight children were born. All of our children died of consumption [tuberculosis]..."

|

|

This photo, from around 1890, shows a log house of the type of construction used by pioneers. The house was built around 1840 and existed for over 100 years on the west side of Main Street, just north of CR 500S. The house, at the time of construction, would have marked an average farming family with enough extra money for a second story. However, as the letter above explains, this would not have been any family's first dwelling. A pioneer family's first shelter would have been a hut. (A photograph of an original one story log cabin, more common to pioneers, is featured on the Union Township history page.) The family pictured is that of John H. Hull, 1850-1917, on the far right, and wife Sarah Jane Langley, 1852-1934, next to him, with their eight children and matched pair of work mules, of which any farming family of the time would have been proud. The photo also shows fruit trees in the left background in contrast to the untouched forest in the right background. Some clearing for fields or pasture is evident in front of the forest's thick undergrowth; barns and sheds behind the house are also discernible. John was a son of settler Obadiah Hull, 1817-1870, and Jane was the daughter of pioneer Curtis Langley, 1806-1875. Madison County pioneers and later settlers were not without some aesthetic sensibilities as evident by the climbing rose beautifying the corner of the house. John and Sarah Hull are buried at the Huntsville Cemetery. This photo, which had historical information on the back, was provided by Don McCune, a descendent of the family. |

Pioneer Veterans

A number of pioneer settlers were also veterans of the Revolutionary War or the War of 1812. After America's fight for independence, the United States government offered land as payment to its veteran soldiers. The majority of veterans took advantage of this opportunity to have farm land of their own. For this reason, much of what had been the Northwest Territory (Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, etc.) was pioneered and settled by family men who had first helped found a nation. The state of Indiana holds over 2000 recorded Revolutionary War veterans. Madison County historians can document twelve Revolutionary War soldiers buried here. Often, family stories, handed down, tell of other patriots who came to Madison County but whose records evidently have been lost. (For pictures and biographical data, see the Revolutionary War Veterans page.)

|

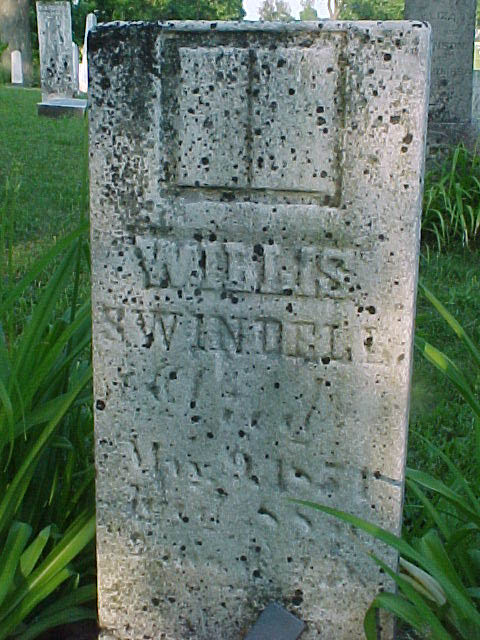

The stone of Revolutionary War veteran Willis Swindell, 1763-1851, is pictured at right. His service is recorded in the Supplement to the DAR Index of Patriots. Of the twelve Revolutionary veterans buried in Madison County, six are in Fall Creek Township, two are in Jackson, two in Union, and one each in Richland and Van Buren townships. Of the twelve, Willis Swindell is the only one with a legible, complete, original stone intact at its original grave site. This stone can be seen at the Old Vinson Cemetery in Van Buren Township. |

|

After the War of 1812, the same payment method--land for military service--was used for those soldiers, and the number of 1812 veterans buried in the county is much larger. The pre-Civil War veterans are spotlighted in red on the individual cemetery pages.

Pioneer Character

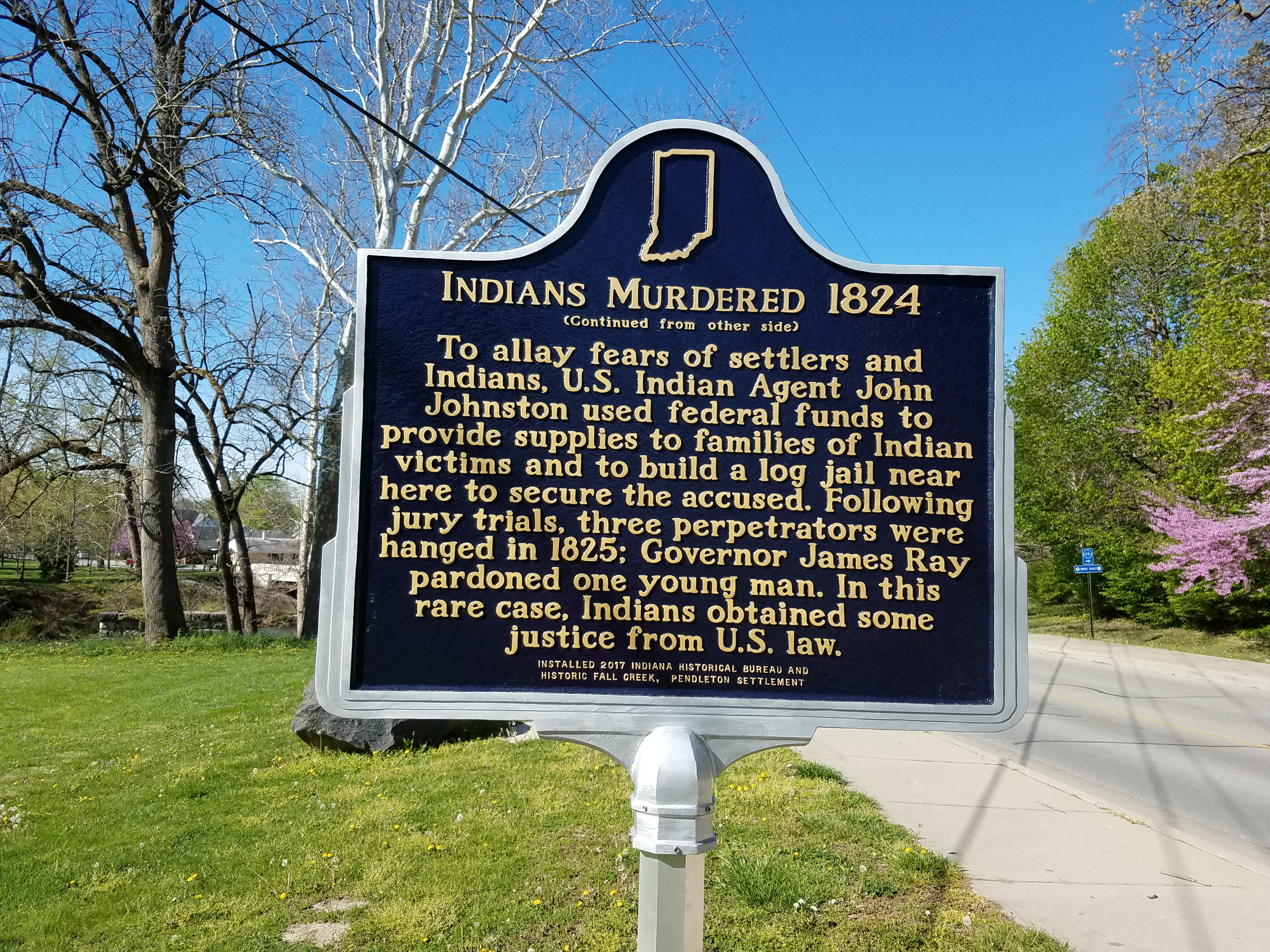

A pivotal event that defines the character of our early settlers occurred in 1824. In February of that year, two families of peaceful Native Americans were camped, hunting and trapping for furs, along Lick Creek about one mile northeast of Markleville in Adams Township. They had been very successful in their pursuits and had obtained a large quantity of pelts. Living in the same area with families were John T. Bridge, his son John Bridge, Andrew Sawyer, James Hudson, and Thomas Harper, hunters and trappers themselves. The white men saw what they thought was an easy way of gaining valuable furs. They worked out a plan to deceive the quiet Native Americans and in the process of carrying out their scheme brutally killed all of them-- two men, three women, and four children under the age of ten, two boys and two girls. Bridge and company then mutilated some of the bodies and looted the camp of any valuables.

The bodies of the Native Americans were

discovered the next day by white settlers on their way to a religious meeting at

the home of Peter Jones. The news of the atrocity spread, and bands of the

white settlers pursued the culprits. All of the suspects were caught and

jailed except for Thomas Harper who escaped to Ohio and was never seen again in the

territory. The four remaining suspects--Bridge, his nineteen year old

son, Sawyer, and Hudson--were indicted for murder, tried by a jury of thei r

pioneer peers, and sentenced to die by hanging. As John Forkner put it in

his 1914 history of the county, "This was the first time, and is perhaps the

only instance in the history of American jurisprudence, where white men were

legally executed for the killing of Indians."

r

pioneer peers, and sentenced to die by hanging. As John Forkner put it in

his 1914 history of the county, "This was the first time, and is perhaps the

only instance in the history of American jurisprudence, where white men were

legally executed for the killing of Indians."

This was only the second term for the Madison County court system, and facilities were very primitive. In April 1824, the grand jury that indicted the accused was held in John Berry's log cabin which stood on the town square in Andersontown in Anderson Township. The jail at that time was a log pen--"a small stockade, made of large poles planted in the ground firmly"-- on the north bank of Fall Creek just below the falls in Fall Creek Township. In October of that year, James Hudson was tried separately and was the first to die for his crimes. He was hanged on December 1, 1824.

A rough log house, measuring twenty by thirty feet, near the jail was used for the court house. As with Hudson's trial, the scene of the trial of the remaining three was complete with court officers, sheriff and deputies, jury, formal proceedings, prosecutors, defense lawyers, on-lookers, and weeping family members. Emotions and tension ran high as all aspects of the trial were the hot topics of moral and political discussions. At the end of the legal proceedings, Judge Eggleston, white faced, read the sentence to the three criminals: "You shall be taken to the jail of the county of Madison, and from thence to the place of execution, on the first Friday of June...between the hours of 10 o'clock in the forenoon and 5 o'clock in the afternoon, be there hanged by the neck until you are dead..."

A scaffold had been built a short distance from the jail by June 3, 1825, the date for the executions. Immense crowds of people gathered on the banks and bluffs of the falls area to witness this landmark event. Among the government officials, interested parties, local citizens, and family members were Native Americans and their chiefs who, themselves, had come to witness the punishment of white men for murdering members of the red race. The rights of Native Americans under the law and the concern for the continued security of the white settlers from retribution had brought James Brown Ray, governor of the state of Indiana, to witness with the tribal leaders the execution of the guilty.

|

Fall Creek with its natural falls was the first area in the county to attract pioneers. John Rogers is generally deemed to be the very first settler; he homesteaded one-half mile east of present-day Pendleton in 1818. By 1825, the year of the executions, the Pendleton area had attracted so many settlers that it looked like a town even though it was not incorporated yet. The executions took placed on the bank left of the bridge in this picture; the stone, pictured below, marks the spot. Today, the falls area is a beautiful city park. |

The adults were executed first-- John T. Bridge, the father, and Andrew Sawyer, his brother-in-law. The son, John Bridge, was to be executed last by himself. Perhaps this was done intentionally because some people were of the opinion that the son, as a minor, would have only been following the directions of the adults and so would not be guilty of premeditated murder. Madison County officials wanted justice for the Native Americans, but they also wanted to give the governor as much time as possible to pardon the young man. Evidently this was a hard decision for the governor to make. At the last minute, with John Bridge, the nineteen year-old, seated on the scaffold, his head in the noose, Governor Brown announced, "John Bridge, stand up. By virtue of the power vested in me as governor, you are pardoned." Everyone agreed with the governor's pardon--including the Native Americans who wanted no more killing of white or red men.

|

|

|

|

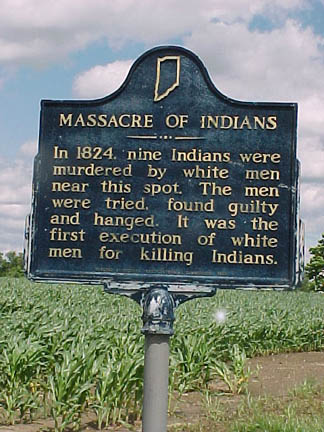

Near the spot where the executions were held stands this Indiana Historic Marker commemorating the event. It is on the north bank of Fall Creek within the city park boundaries. The hill whereon stood both white settlers and Native Americans as witnesses is just across Pendleton Avenue. This area is now the location of beautiful Victorian homes. To the left is the first side of the text; to the right is the conclusion.

Early pioneer civilization had thus rendered its verdict: laws are made to protect everyone, "even Indians." Justice and mercy prevailed in this instance. The Indiana dark blue historic marker, pictured above, commemorating the massacre and its outcome is located on the north side of SR 38 just east of Markleville.

A full account can be found in the 1880 History of Madison County, Indiana, pages 39-41. The story has action, tears, courtroom drama, fights, escapes, mystery, insanity, and tension right to the end--the perfect story for a movie. This milestone in United States jurisprudence has already been used as the basis for a novel, Massacre at Fall Creek by Hoosier author Jessemyn West, and has granted Pendleton a place on the National Register of Historic Places. (Pioneer history continues on the Fall Creek, Union, Jackson, Stony Creek, Anderson, Adams, Green, Lafayette, Monroe, Richland, Pipe Creek, Van Buren, Boone, Duck Creek township pages.)

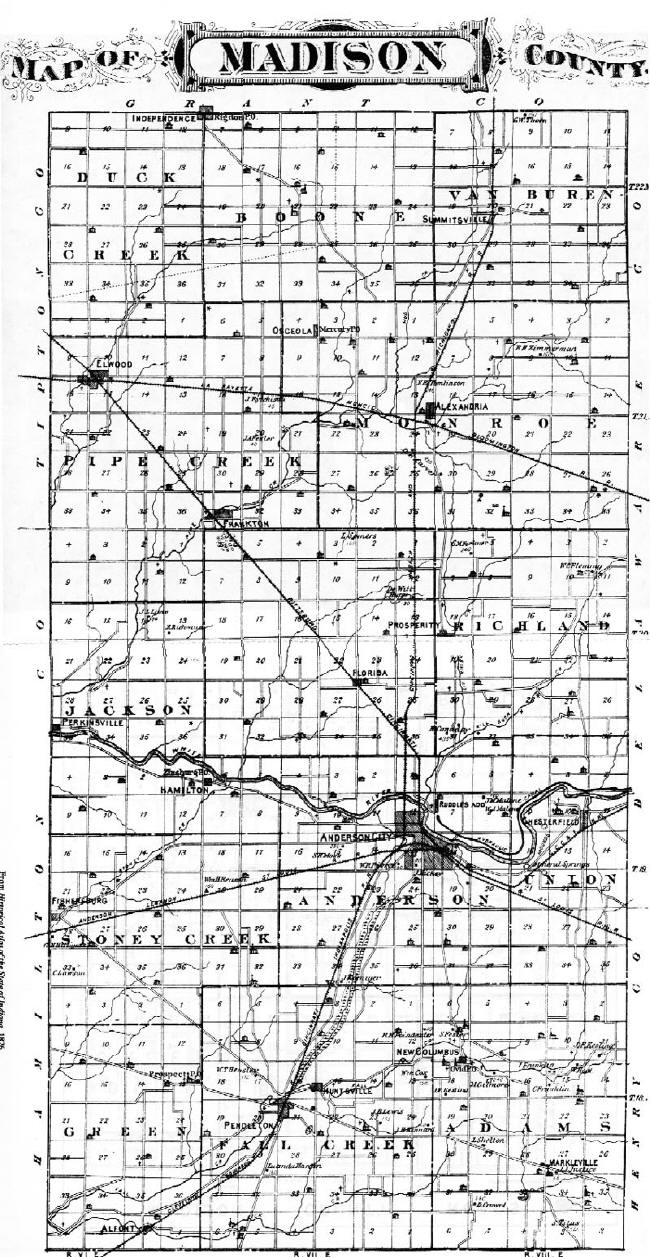

|

This is what Madison County looked like in 1852, only thirty-one years into the official opening of the New Purchase and twenty-nine years after Madison County's legal organization. Madison was one of the first counties developed in the New Purchase. The county seat is very small and still named "Anderson Town." Several smaller villages still exist like Forrestville and Hamilton, and others go by different names like New Columbus and N. Madison. Two railroads have been laid, and some major pioneer traces have been made more passable and so are marked as roads. From "Map of the state of Indiana compiled from the United States surveys by S.D. King, Washington City; exhibiting...the situation &boundaries of counties; the location of cities villages & post offices, canals, rail roads and other internal improvements, carefully laid down," it should be noted that the small and larger squares are not roads, but merely designate how the forested, still thinly populated land was divided into sections and ranges. |

|

From a Private Responsibility to a Larger Public Business

When someone in the pioneer family died, the family took care of their own. The living would choose a remote area on the property as the family graveyard. The plot was often on a hill, if one was available, because hills were "closer to heaven" and difficult to plow. Since waterways cut into the land creating steep banks and hills over eons, those graveyard hills were many times next to rivers and creeks. Once a family graveyard was begun, it would often be used by the neighboring settlers if they had not begun one themselves. The story of the Gilmore illustrates how one death in a family began the burial ground for a larger group of early 19th century settlers.

|

Pictured (2004) at right is a rarity: an original pioneer log cabin. It has been attractively painted and has modern additions attached in the back, but it is still used as a residence. A Madison County treasure, the Solomon Fussell (c. 1790-1849) pioneer house, built in 1832, is east of Pendleton on one of the earliest roads, the Pendleton-New Castle Pike (SR 38). This log cabin is recorded on the National Register of Historic Places. |

|

Community-oriented pioneer cemeteries were placed along pioneer roads. These roads were actually, by modern standards, dirt trails, the route of which was dictated by topography: the easiest way for walking along a river, around a swamp, or at the base of hills. Hash marks cut or "traced" in the trees lining the path indicated directions. These "traces" afforded the pioneer the only access to a destination via land. Consequently, towns, churches, and some families would locate their burial grounds along or off a trace. Many modern Hoosier highways that wind around and over natural features began as traces and when widened into graveled trails were referred to as "pikes." Strawtown Pike (White River Road, South Bank Road, West 8th Street, 8th Street), Pendleton Pike (SR 9, Martin Luther King Boulevard), Anderson-Alexandria Pike (Alex Pike, SR 9), Fort Wayne Trace (destroyed), Indianapolis-Pendleton Pike (Indiana Highway, Reformatory Road), and Pendleton-Newcastle Pike (SR 38) all have settlers' cemeteries gracing their borders.

|

|

This Federal style brick home, built in 1829, faces the most heavily traveled pioneer road in the county: South Bank Road/Strawtown Pike, now designated as West 8th Street/8th Street. Because this road was one of the few recognizable trails into the western sections of the New Purchase, hundreds of settlers would have had to pass along the front of the Daniel Wise home, pictured above. Daniel Wise, 1792-1848, came from Ohio with his family to Jackson Township in 1822. The Wise family farmed the land along White River just east of Perkinsville. While Madison County pioneers may have had to start with only a hut for shelter, a few of them, like Daniel, eventually became wealthy enough farmers to afford a luxury: a brick house. The bricks would have been baked on location, and the wood hewn from surrounding forests. The brick house in the early 1800s was the mark of financial success. This beautifully reappointed home is lovingly cared for today by its present owners. Daniel Wise, his family, and generations of his descendents are buried at the Perkinsville Cemetery. (For more on the Wises, go to the Perkinsville Cemetery page.) |

The first organization that pioneering families in a locality desired was a fellowship of like-minded religious believers--a church. Initially unable to afford the expense of a separate building for worship, the congregations held meetings in each others' homes. Many times, a member would donate a plot of his land to be used for the congregation's burial needs. When a congregation could afford to construct a separate building, most often a member would donate the land for both the church and the customary adjoining cemetery. Methodists, Baptists, Lutherans, Friends, United Brethren, Catholics, Wesleyans, New Light/Christians, German Baptists, etc., are all represented in Madison County pioneer history through their cemeteries.

|

The Cornerstone Community Church, located on the southwest corner of CR 1300N and CR 200W in Monroe Township, is pictured left. Cornerstone is the heir to the pioneers' Lily Creek Baptist Church, which began at this location in the mid 1800s. The Baptist church is shown on the 1876 plat map for the township. One mile north of the Lily Creek Cemetery, Cornerstone, like its predecessor, serves a rural community of farming families. After securing a homestead, churches were the first community organization that pioneers desired. |

When towns were laid out in the first half of the 1800s, there was, of course, the need for a place to bury the dead. Perkinsville, Anderson, Pendleton, and Fishersburg had "city" cemeteries, a place where anyone living in or near the community could be buried. Toward the last part of the 19th century, there developed the cemetery association. This is when burying the dead became big business. Associations took over the care of what had been older city cemeteries. The business would add grounds, beautifully maintain both the old and the new, and in so doing, preserve a portion of the past in a setting that would essentially be a sacred park. Maplewood, Grovelawn, and Brookside began this way. Even when a pioneer village, like Forrestville or Mendon, failed to develop and gradually disappeared, its residence for the dead would often remain as part of a modern business, preserved, protected, and used. Many of the small, once remote, family graveyards like the Bronnenberg, Vinson, Waggy, and Williams were also incorporated into businesses in the later 19th century to serve a growing nearby community or developing modern neighborhood. Other pioneer cemeteries would not be that fortunate. (For more, go to Archives & Laws.)

|

Record of the earliest death date on a legible headstone in any Madison County cemetery is that of Mary Kerr McClintick. Her stone reads, "Mary, wife of Alexander McClintick, died Aug. 12, 1821, 43y 7m 11d." She and her husband Alexander, 1763-1848, McClintick/McClintock helped settle the wilderness along White River near Perkinsville in Jackson Township. Many generations of this family are represented in the well-preserved old section of Perkinsville Cemetery. Like Grovelawn and Maplewood, the Perkinsville started as the graveyard for the nearby settlement and was later incorporated into a burial business. (For more on the McClinticks, go to the Perkinsville Cemetery page.) While this stone records Mary's death, it is not the original grave marker--if, in fact, Mary had one at all. Since the stone is a soft white marble popular in the mid 1800s, this is a replacement stone erected by later family members to honor their ancestress. In the 1820s, a brown hard sandstone was used for grave markers. If not sandstone, then a rough field stone or wood might have been used. This stone does witness to the fact that family history is not a new hobby. Genealogy has been of importance down through the ages. |

1876 Maps

Since the Madison County Court House burned in 1880 and many valuable records were destroyed, the MCCC has provided 1876 plat maps for each township to help historians and genealogists. Many of the pioneer cemeteries are indicated with a little cross. Click on the township name above or below to go to that township's history page and 1876 plat map. Each township page provides a continuation of Madison County's pioneer history along with a list of early settlers and their cemeteries.

|

|

![]()

This site was last updated 05/15/21