|

Pioneer

Cemeteries and Their Stories, Madison County, Indiana |

|

|

Pioneer

Cemeteries and Their Stories, Madison County, Indiana |

|

The New Purchase

The larger area that included what is now Madison County was opened for settlement when Native Americans of the Delaware and Miami tribes ceded their lands in Indiana to the United States government in the Treaty of St. Mary's, October 3, 1818. While the Native Americans were allowed to stay for three years before moving west, pioneers from the East began arriving to homestead the "New Purchase."

The nadir of the southern boundary of the New Purchase as shown on the map at right is located in what is now Brown County. An Indiana Historic Marker explaining this point is located on SR 135 along the southern boundary of Brown County State Park and just east of Story, Indiana. The marker explains the "10 O'Clock Line." This was the name of the boundary line of the lands purchased from the Miami Native Americans by territorial governor William Henry Harrison September 30, 1809. Nine years later, this line would form the southwestern boundary of the New Purchase. The eastern and southeastern boundaries had already been established by previous treaties. The New Purchase opened for settlement to whites the central section of Indiana which included what is now Madison County. The descriptive name, "10 O'Clock Line," is in the parlance of frontiersmen and Native Americans. The line follows the shadow made by the sun at 10 o'clock on September 30th. The boundary in modern terminology starts near Montezuma, Indiana, on the Wabash River and runs southeast to the mouth of Raccoon Creek near Seymour, Indiana.

Lenni Lenape/Delaware

Wapihanne/White River

|

|

This is what pioneers to the eastern half of the New Purchase faced in the early 1800s: an untouched forested wilderness sprinkled with Delaware villages along the only trail and major waterway. From the 1932 map entitled Indiana The influence of the Indian upon its History-with Indian and French names for Natural and Cultural Locations, #122, published by the Indiana Department of Conservation, the White River area of Madison County is shown as a well-developed part of the larger Delaware society in east-central Indiana. The Delaware had as many as fourteen villages along this west fork of the White River. The Delaware--or Lenni-Lenape, meaning "real men"--were living along the East Coast in what is now the state of Delaware at the time of the first discoveries of the New World. As the white civilization advanced, the Delaware moved westward, living near Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1682, on the Susquehanna River in 1742, in eastern Ohio in 1751, and being invited by the Miami and Piankeshaw tribes to settle between the Ohio and White rivers in 1770. Many modern place names in east-central Indiana are either Delaware names or their English equivalents: Muncie, Wapihanne, Killbuck, Kikthawenund, and Anderson. The map shows the Wapihanne--or White River--flowing westward past the Delaware villages of Munseetown, Buckstown, Andersontown, and Straw's Town before turning south and reaching the first white settlement in east-central Indiana, the William Conner farm of 1802 where the Conner Prairie historical recreation now exists. Continuing south, the White River passed what would eventually be Indianapolis, or Chanktunoongi meaning "makes a noisy place" in the Miami tongue. The triangles indicate Delaware villages, the circles mark white settlements, and crosses are religious missions. Even before William Conner settled on his farm in 1802, white Moravian missionaries had located in Madison County in 1801. The White River's major tributaries are clearly shown: Fall Creek, Pipe Creek, Killbuck Creek, and Duck Creek where pioneers would settle starting in the southern half of the county and eventually moving into the northern. The dotted line along the north bank of the White River is the well-established Indian trail going from what is now Greenville, Ohio, to Chicago, Illinois. Using ox-drawn wagons and possibly pack horses, this would have been the route most of the first pioneers coming from the East would have taken into the Madison County section of the New Purchase. The northwest corner of the county was part of the Miami Indian Reservation as marked by the line of dashes. The county seat of Anderson began as a Delaware village called Wapiminskink meaning "chestnut tree place" and later referred to as Andersontown after Delaware Chief Anderson. The original layout of Anderson followed the Delaware village's boundaries and trails. (For more on Anderson, go to the Anderson Township page. |

|

These "monarchs of the forest," now tipping with age into the water of the Wapihanne (White River), might well have seen the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) paddling their canoes between Buckstown (near Chesterfield) and Wapiminskink (chestnut tree place, Andersontown). This picture was taken in Edgewater Park in Anderson. Along the opposite bank in the background was the location of the original Delaware village and later settlement of Andersontown. |

|

Kikthawenund/Chief Anderson

|

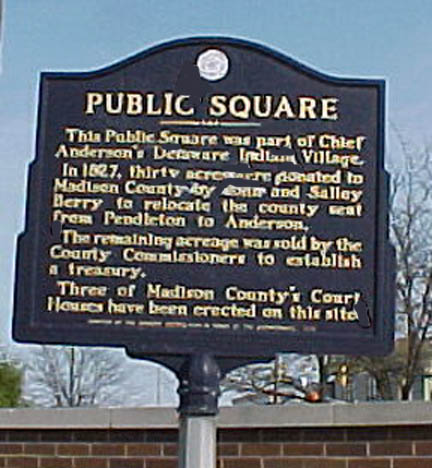

This Indiana Historic Marker sits in front of the Madison County Court House at the southwest corner. The marker reminds Andersonians: "This Public Square was part of Chief Anderson's Delaware Indian Village. In 1827, thirty acres were donated to Madison County by John and Salley Berry to relocate the county seat from Pendleton to Anderson... Three of Madison County's Court Houses have been erected on this site." |

|

Anderson Township was one of the first five townships created in the county. It and the county seat of Anderson derive their names from Chief Anderson, the English name for Kikthawenund, who was the primary leader of the Delaware tribe. The Native American name for this group is the Lenni Lenape, meaning the "real men" or "ancient ones." The Lenni Lenape were revered by other tribes of Native Americans. The Lenni Lenape called their village, which later became Anderson, Wapiminskink, meaning "chestnut tree place." Kikthawenund's individual camp was located at what is now the 900 block of Fletcher Street.

Kelelamand/Chief Killbuck

|

The rich farm land of Richland Township is drained by Killbuck Creek, pictured right. Like many other place names in east-central Indiana, Killbuck is the English equivalent of a Delaware name. Chief Kelelamand or "big cat" had the English name Charles Henry Killbuck (late 1700s-early 1800s). His father was the chief who took over after the death of White Eyes in 1778. Chief Killbuck had a village which white pioneers referred to as Buck's Town. It was one mile northwest of Chesterfield on a high bluff over-looking White River. The chief was one of the Native Americans converted by the Moravian missionaries who had begun their work in the area in 1801. Chief Killbuck signed the Ft. Wayne, Indiana Treaty of 1809 and the St. Mary's, Ohio Treaty of 1818. Chief Killbuck was a respected Delaware figure among Madison County pioneers and early settlers. |

|

Tahunquecoppi/Chief Pipe

Pipe Creek Township, like several other townships in Madison Coun ty, is named after the tributary that runs through it--Pipe Creek.

The creek, however, is named for the Delaware leader Chief Pipe,

also called Captain Pipe. One of his Delaware names was Tahunquecoppi

meaning "Tobacco Pipe." Chief Pipe was born in the mid

1700's, is documented as living in what is now Ohio, signed several treaties,

and died around

1818. He was famous as a war chief who sided with the British during the

War of 1812. According to local folk history, Chief Pipe eventually

resided with his branch of the Delaware near what is now the village of Orestes

in Monroe Township to the east of Pipe Creek Township. Chief Pipe, Tahunquecoppi,

also, according to the story, died at Orestes and is buried there.

ty, is named after the tributary that runs through it--Pipe Creek.

The creek, however, is named for the Delaware leader Chief Pipe,

also called Captain Pipe. One of his Delaware names was Tahunquecoppi

meaning "Tobacco Pipe." Chief Pipe was born in the mid

1700's, is documented as living in what is now Ohio, signed several treaties,

and died around

1818. He was famous as a war chief who sided with the British during the

War of 1812. According to local folk history, Chief Pipe eventually

resided with his branch of the Delaware near what is now the village of Orestes

in Monroe Township to the east of Pipe Creek Township. Chief Pipe, Tahunquecoppi,

also, according to the story, died at Orestes and is buried there.

Nantikoke/Chief Nancy

The Lenni Lenape/Delaware tribe's villages stretched along White River in Delaware, Madison, Hamilton and Marion counties. Charles Thompson, in his 1937 Sons of the Wilderness: John and William Conner, records one of their villages as existing close to the river's south bank somewhere in Jackson Township's section 1 or 2. This area was called the "the McClintock neighborhood" by several early 20th century historians who also discussed this Delaware village. Nancy's Town/Nancytown was the name given to it by white settlers as a corruption of Chief Nantikoke's name. The exact location of Nancy's Town is not pin-pointed, and the village does not seem to have had the same importance as those of chiefs Anderson, Killbuck, Pipe, and Munsee. Additionally, Nancy's Town did not exist as long as the others since there are some sources that confuse it with Straw's Town in Hamilton County.

Events Involving Other Tribes

Strawtown Massacre

Benjamin Fisher was a veteran of the War of 1812. Benjamin has the distinction of being one of the few white settlers actually killed by the Native Americans remaining in the area. An article titled "Early Settlers" from an unidentified Lapel newspaper published in October 1903 tells of the family's migration to Stony Creek and the events which brought about Benjamin's death:

"Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Fisher, from Clermont County, Ohio, in June of 1820...in a wagon came to Indiana. They drove through Winchester to Anderson, Indiana, the latter place being then merely an Indian Village, with no white people living there. The old chief Anderson, for whom the town was named, was living there at the time.

"They drove down the river...between Perkinsville and Strawtown and there settled in a round log cabin 16 feet square, in which was no floor but the dirt.

"In Strawtown...was one white family named Shintapper. This man kept liquor to sell to the Indians and when they bought the liquor and got drunk Shintapper would abuse them. He had a great fireplace in which logs six feet long could be burned and he once threw an Indian on this fire where he was burned to death. At another time he burned one until he was crippled afterwards.

"By such treatment the Indians were justly incensed and determined to be revenged and so ten of them went one day armed with their knives and tomahawks, intending to kill Shintapper when no one was about.

"That same day--in March, 1821--Benjamin Fisher, John Colip, and Jacob Hiers happened to go to Shintappers to grind their axes, he being the only one in that settlement who owned a grindstone. They had not been there long before the Indians arrived. Of course they could not stand by and see Shintapper killed so undertook to defend him.

"There was a five-rail fence around the cabin, outside of which were the Indians and inside were the white men. ... The battle then continued as at first, the red men retreating and the white men chasing them, then in turn being chased back. Finally one Indian hit Shintapper with a club and knocked him down, then jumped on the fence to get inside. At this Hiers struck the Indian on the head and killed him...Then the battle waged fiercer than ever. But when retreating from the Indians Benjamin Fisher fell and was at once tomahawked by the Indians, who then gathered up their dead Indians and went away. Mr. Fisher was not scalped as some accounts have stated but from the pieces of skull (now in possession of [son] Charles Fisher) it is evidenced that he was truck several times with the tomahawk.

"That same night Shintapper loaded his goods in a canoe and with his wife and child went down White River and was never heard of again. Benjamin Fisher was buried at Strawtown near where he was killed. His was the first grave in what is now known as Strawtown Cemetery."

Stony Creek Township Incident

The same article as above also tells of another dangerous encounter with the local Native Americans which Benjamin's wife had some years later at the family's Hoosier frontier homestead:

"The Indians used to be daily visitors at their [Fisher's] house. His [son Charles'] mother had a large pewter basin that held about two gallons; in this she would put a generous quantity of milk, break in bread and putting down as many spoons as there were Indians, let them seat themselves on the floor around the bowl and eat.

"One time four of five Indians came, one or two of them being the worse for liquor. Mrs. Fisher was sewing with the children playing about her. The Indians asked for food. She told them that she did not have any. At this one of the drunken Indians took hold of her hair and taking out his long knife, run the back of it around her head saying, 'me scalp white woman.' The two older children ran out to call in a man who was chopping nearby, while young Charles darted under the bed. When the man came in from outside, he reached up and took down one of the guns in the cabin, when the Indians run out, mounted their ponies and rode away."

Union Township Incident

An article, titled "Historic Taverns," from an

unidentified local newspaper, dated November 18, 1901, relates the importance of

this early 19th century structure and an early example of responsible

bartending:

"The old tavern...is one of the largest and most substantial residences in this part of the country. When it was built, about 1830, it was the only brick building in Madison County, and people drove all the way from Indianapolis to see it and spend a night in the famous tavern. At the time that Mr. Dilts built the tavern, Indians were still plentiful in this locality, and though usually peaceable, they sometimes became quarrelsome when able to secure all the 'firewater' they wanted. At one time a party of them called on Mr. Dilts. They had already been drinking too much, and Mr. Dilts refused to let them have any more. They became angry and would have killed the old landlord had it not been for the presence of mind of his wife, who hid him in the cellar."

Fortunately, attacks by Native Americans in the Madison County wilderness were actually rare, so much so that the one or two violent acts remained memorable in settlement history.

Lafayette Township

According to mid 20th century MCCC archives, a Native American burial ground once existed in the middle of what is now Florida Station, specifically between the railroad and CR 375N on the east side of CR 200W. This location would place the burial ground at the only crossroads of the small hamlet. While there exists no written record of this burial site's location or even existence, sometimes the stories and remembrances handed down in families, or in this case to historians, are the only pieces left of a site's or people's history. Evidently, at some point in the early or middle part of the previous century, a Madison County Historical Society member was told by a knowledgeable and reliable source that local "Indians" once used this spot to bury their dead. Perhaps the story developed when the railroad was being constructed, since it is next to the site, or when the last Native Americans in Madison County migrated west in the 1830s or when Florida Station was being planned and built. Maybe the station's designers did not want to desecrate hallowed ground. The burial site does not have any buildings on it but appears to be the side yards of houses built along CR 375N. However the story was handed down, the MCHS, at the time, regarded the folk history with respect and recorded the burial ground's location for future reference.

Law and Order

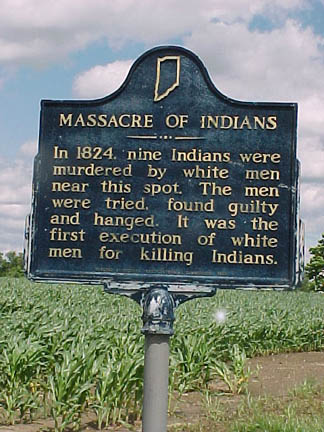

A pivotal event that defines the character

of our early settlers occurred in 1824. In February of that year, two families of peaceful

Native Americans were camped, hunting and trapping for furs, along Lick Creek

about one mile northeast of Markleville in Adams Township. They had been

very successful in their pursuits and had obtained a large quantity of pelts.

Living in the same area with families were John T. Bridge, his son John Bridge,

Andrew Sawyer, James Hudson, and Thomas Harper, hunters and trappers themselves.

The white men saw what they thought was an easy way of gaining val uable

furs. They worked out a plan to deceive the quiet Native Americans and in

the process of carrying out their scheme brutally killed all of them-- two men,

three women, and four children under the age of ten, two boys and two girls.

Bridge and company then mutilated some of the bodies and looted the camp of any

valuables.

uable

furs. They worked out a plan to deceive the quiet Native Americans and in

the process of carrying out their scheme brutally killed all of them-- two men,

three women, and four children under the age of ten, two boys and two girls.

Bridge and company then mutilated some of the bodies and looted the camp of any

valuables.

The bodies of the Native Americans were discovered the next day by white settlers on their way to a religious meeting at the home of Peter Jones. The news of the atrocity spread, and bands of the white settlers pursued the culprits. All of the suspects were caught and jailed except for Thomas Harper who escaped to Ohio and was never seen again in the territory. The four remaining suspects--Bridge, his nineteen year old son, Sawyer, and Hudson--were held for murder, tried by a jury of their pioneer peers, and sentenced to die by hanging. As John Forkner put it in his 1914 history of the county, "This was the first time, and is perhaps the only instance in the history of American jurisprudence, where white men were legally executed for the killing of Indians." (For more on this pivotal, historic event, go to the Madison County history page.)